Craft Wednesday: "I’m allergic to hair dye and silver."

Listening for sound patterns in Hala Alyan's "Truth"

I love this poem.

Hala Alyan pulls off a magic trick—a careful choreography of confession-speech, music, and resonance. The poem draws me slowly, deceptively-easily through an arrangement of plainspoken diction, hyper-clear images, and uneasy associations. Alyan leaves me with a palpable ache. Part of me wants to say that’s what it is: magic, pure and simple. And Alyan is the sort of devastatingly good poet that its tempting to not even, you know, try to learn from her. But hey: I also hope to pull off some magic in my poems, so I guess I should look a little closer and see if I can divine how she makes this poem come to such life. So let’s see if we can figure out some of what makes this poem tick. Tick, trick, magic, music, ache: I think the craft lesson I divined in Alyan’s “Truth” lives in those words I found myself using just now. But we’ll get that later.

A few observations to get us started.

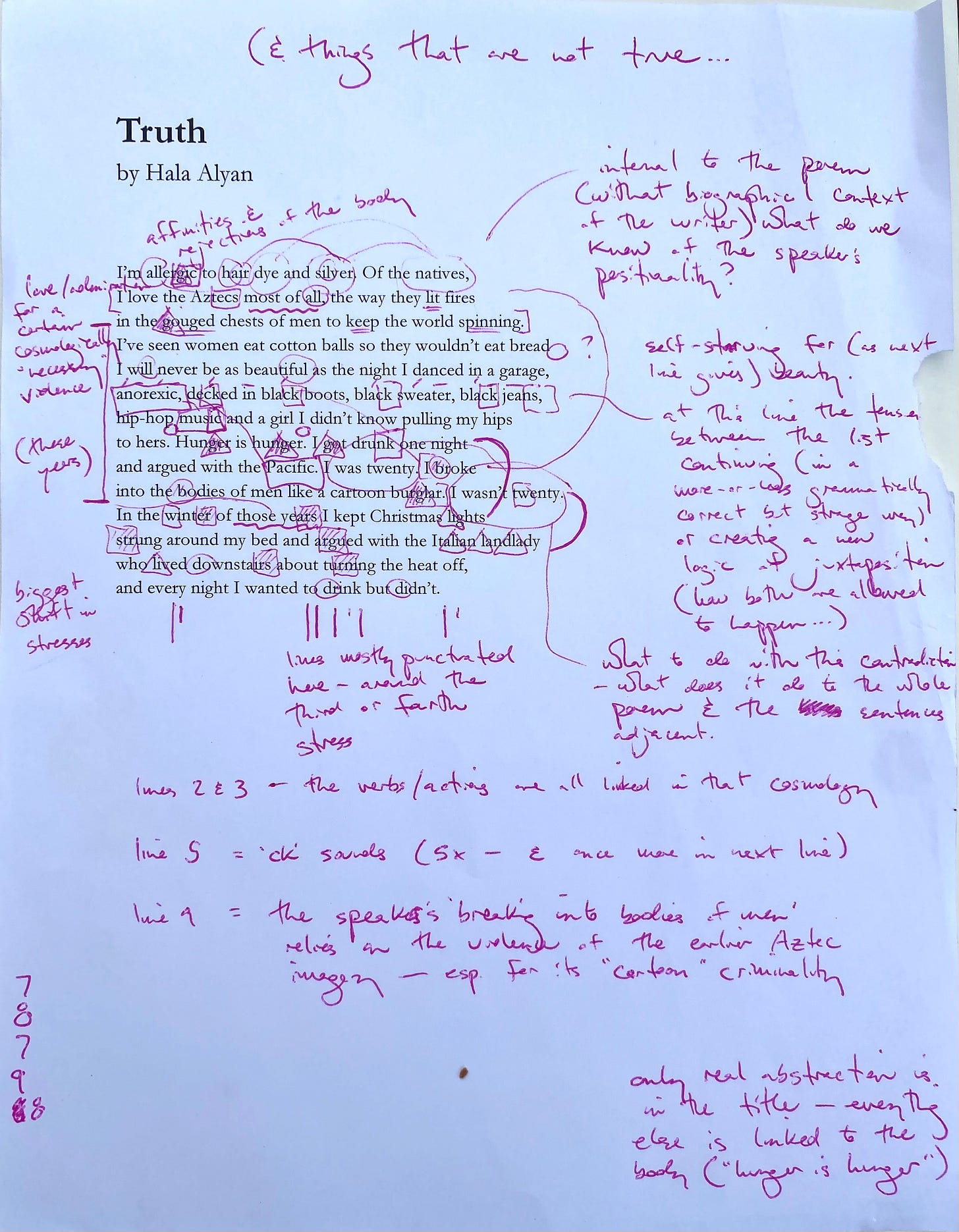

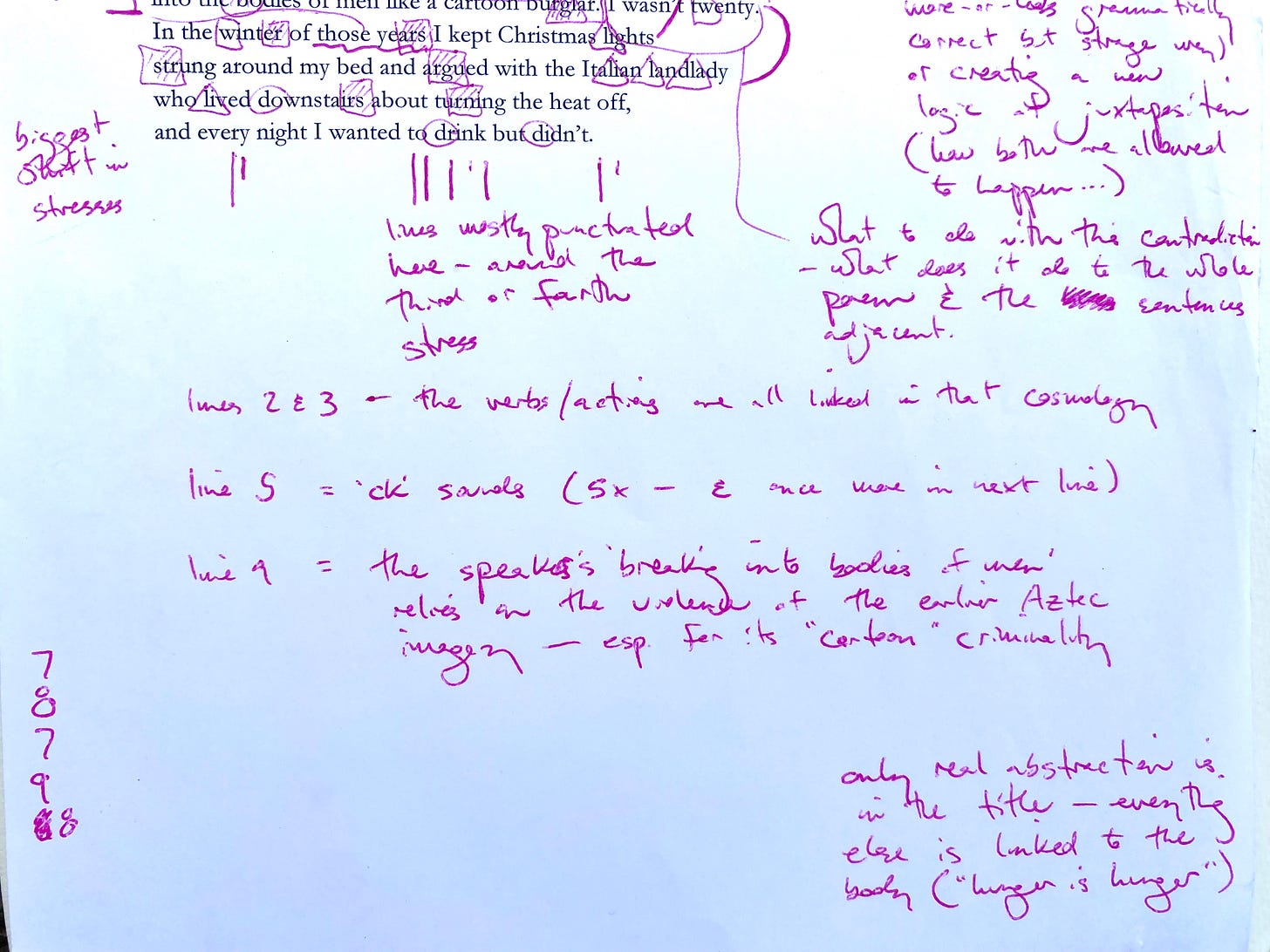

“Truth” is a sonnet—or at least Alyan has, in making the poem a sonnet-y block of fourteen lines, decided to not chase us away from sonnet associations. Arguably, there’s little else in the formal aspects of the poem that tries to nail this association down: only two lines (10 and 12) have end-word slanting rhymes (“twenty” and “landlady”); pentameter there ain’t (lines hover around 7-8 stresses, save for a notable variation of 5 stresses in the final line), nor is there any favored metrical foot; and there’s no volta. Still: I can’t escape the sense that the poem is saying “read me with your sonnet-colored glasses on.”

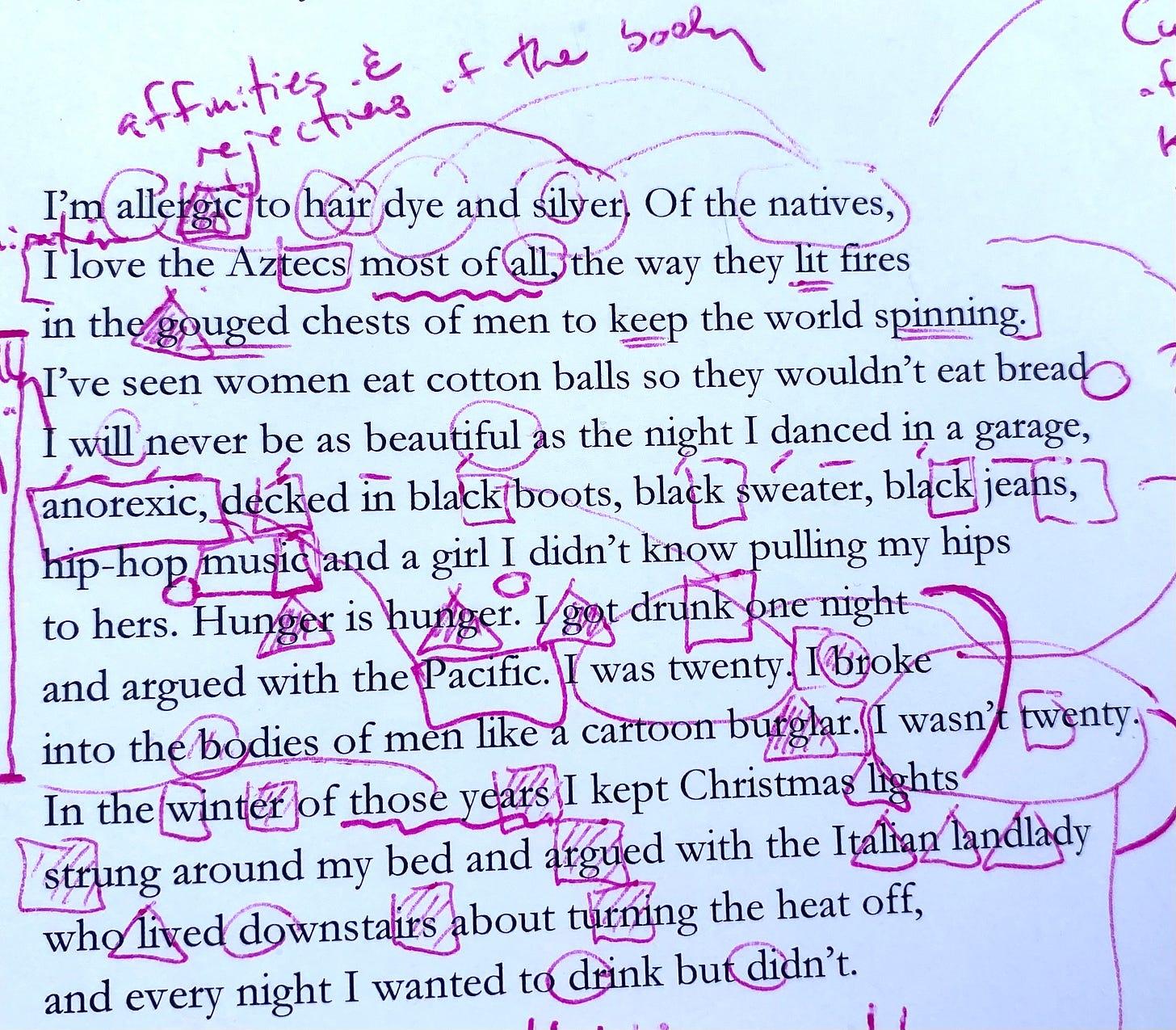

The speaker’s diction is consistent, and consistently conversational. The exceptions to this form a curious clutch of words: allergic, Aztecs, anorexic, Pacific. (And maybe gouged? Gouged is a strange word. Let’s leave that to the side for the moment.) Two of these words ground us in the body: “allergic” and “anorexic.” Each word suggests an embodied rejection: allergies are physiological, not chosen; anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder involving rejection of food and a disturbed sense of body image. Each, depending on a variety of factors, can involve intense fear and result in serious physical harm.

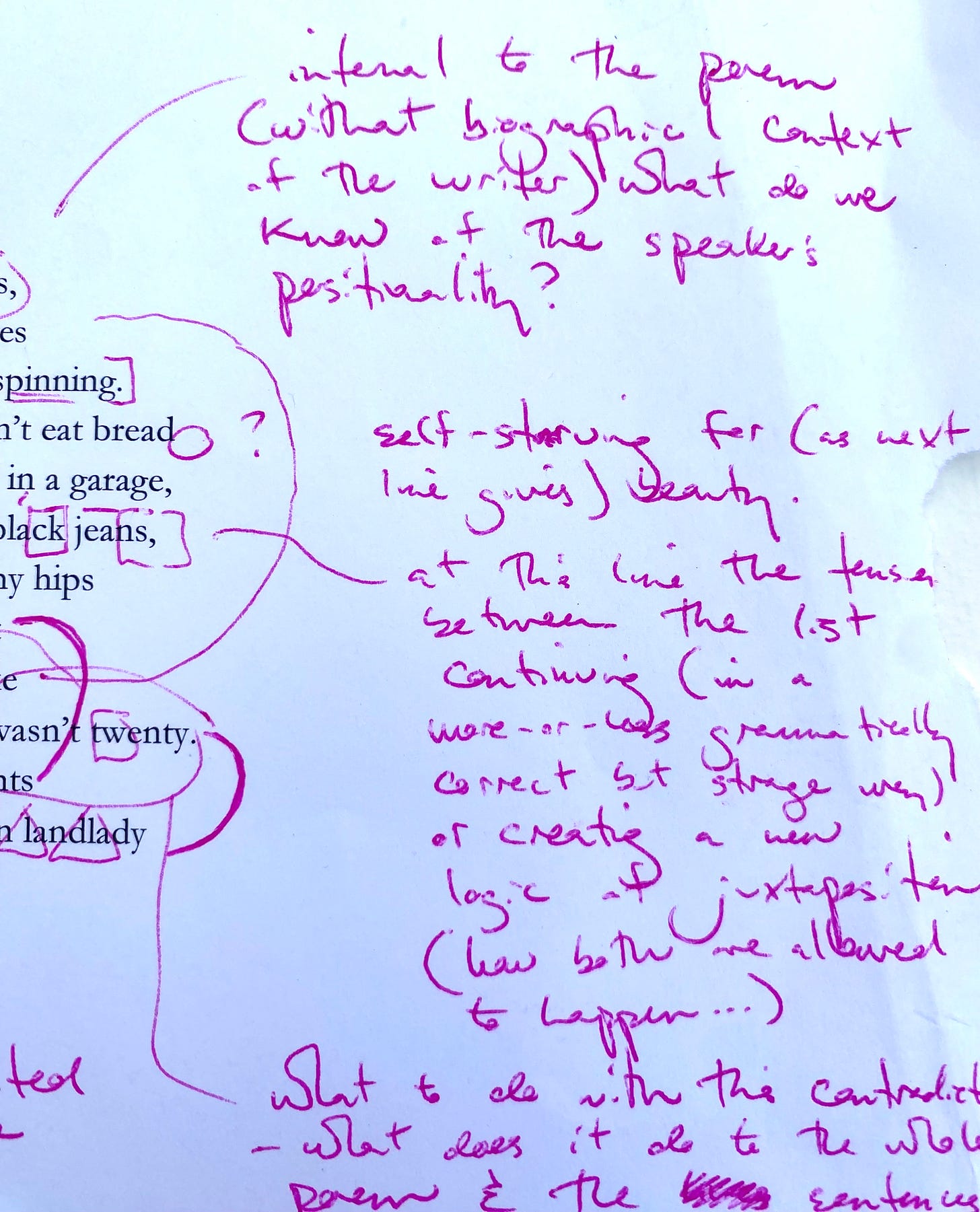

“Aztecs” and “Pacific” together draw us toward North American history. “Aztec”—especially in light of the word “natives” used in the line before—suggests a flurry of associations having to do with pre-contact civilization, genocide and loss, and ceremonial warfare and human sacrifice. Alyan is no doubt all-too-aware of the historical material she is working here: she’s crafted a speaker at an uneasy edge of stereotypes inherited from Spanish conquistadors, and a distinction between “native” and either/both foreigner or settler-colonist. In this light, the resonances in “Pacific” seem to cluster around the ocean’s naming (by Magellan) as part of the unfolding settler-colonization in tension with its literal meaning: calm, peaceful. The mythstory of Magellan’s encounter with the Pacific as relaxed and calm is in contrast with both the actual history (genocide and conquest)of the region, and Alyan’s speaker’s own immediate interaction with the ocean in the poem: “I got drunk one night / and argued with the Pacific.” This constellation of diction becomes an important touchstone for the way we seem to being asked to read and experience the other elements of the poem.

The “truth” of the title is the only abstraction in the poem that isn’t directly grounded or yoked to images involving the body in the surrounding phrases/lines. The sentence “Hunger is hunger” is certainly enigmatic and conceptually charged; but it can be easily read as a culminating reflection emerging out of the women eating cottonballs, the speaker’s identification of themself as anorexic, and the sexual desire of the woman dancing in the garage. The problem of beauty—of being “beautiful”—also haunts the poem, but Alyan endows the description of the speaker’s dancing in the garage with a sort of acme of “beauty”: the ultimate, never-to-be-achieved-again state of being beautiful. But “truth”—truth hangs over the poem without ever being explicitly engaged. As such, Alyan seems to be asking the reader to keep that word—and its possible meanings—suspended throughout the poem. Perhaps we test each sentence’s claims against this possibility of truth; perhaps we test the converse of the sentences (what would it be to not be allergic to hair dye and silver?). Perhaps we wonder how the amalgamation of these statements and images across the poems resolve into a state of being true, or perhaps its opposite.

Lastly—before we return to the trick etc—I think we have to talk about the way that bodily needs and violences intersect. Hungers—for food/booze, for other human bodies and what they contain—are essential to the poem. But notice how so many of these hungers are rendered in relation to violence. The speaker says “I love the Aztecs most” because of the strange, violent image of fires being lit in the “gouged chests of men”—it’s hard to read this as anything other than practice of human sacrifice carried in the word “Aztec.” This doubled violence—first opening another’s body, then setting a fire there—inflects the casual rendering of the self-starving in the next lines. To eat cotton to fool the body into not needing bread—this is a violence. The sexual desire of “a girl I didn’t know pulling my hips to hers” is shadowed by the bittersweetness of the speaker’s past beauty and their anorexia. Curiously, the image that returns us to both sexuality and human sacrifice—“I broke / into the bodies of men like a cartoon burglar”—injects a comedic tone into the mix. I admit to finding myself caught between reading this as further violence, however comedic (a burglar breaking into a bank vault), and a different sort of cat-burglar slyness and quiet. Each of these needs, these hungers, seems linked to a need to “keep the world spinning,” I think. There is an urgency of maintaining or coping with things.

But—and this is what I really want to talk about, however briefly here at the end—how does Alyan manage to create a unified, lyric experience out of all of this?

I’d like to suggest that she does it through the clever use of the sound /k/. This sounds a little absurd, I know. But once I saw it, I kinda couldn’t unseen it—and can’t escape the sense that its part of the achieved musical magic and artistry of the poem. At some point in the drafting process, Alyan seems to have realized—consciously or no—that she had this recurring sound. And like figuring out that the song you are picking out on the piano is in the key of C#, she leaned into what that opened up for the poem’s language. Watch how “allergic” suddenly is pulled toward “Aztec” and “chest;” and then how “anorexic” picks it up and plays it through “decked” and three “blacks,” into “music,” and then “drunk,” and then “pacific” and “broke,” all the way through to “Christmas” and finally “drink.” If we think of this /k/ sound as the poem’s “tonic” (the tonic being the note a particular musical key is built around, returns to most often), we then also begin to see-hear the other sounds/notes that contribute to this key. The note of /g/ emerges out of “allergic” and is picked up in “gouged,” “garage,” “girl,” “hunger” and the repetition of “argued.” And /d/ wends from “dye” through “danced,” “decked,” “didn’t,” “drunk” all the way into, crucially, “drink” and “didn’t.” These three sounds start to form little chords, little constellations that buttress and highlight each other—creating a current of sound that adds resonance and significance to the words that contain them.

To be clear: I don’t think this is Alyan’s secret interest or desire—to realize we are living in the key of /k/ with dominant /g/ and subdominant /d/. But I do think that this patterning is—if not intentional—an essential part of the poem’s DNA: what makes it sing, and what allows the power, the—wait for it: ache—to come through so palpably in the end. I think this one element, this echoing became—by strict design or happy, chanced occurrence—what lifts this poem off the page and into my need for it.

In each of these craft essays, I want to leave us all with something to practice in our own writing and reading of poems.

So: when you’re reading other poems keep an ear out for these currents of dominant sound. Do you find other poems that work similarly to Alyan’s—where an almost invisible pattern of sound knits the poem’s other imagistic, lyrical, or narrative gesture?

And for your own writing: take a poem that’s in an early draft stage and do a close reading of it for sound—alliteration, consonance, assonance. Track three or four sounds that—you now realize—have emerged in this draft as omnipresent.

Then , try the following:

Generate a new collection of words that play with these sounds in unusual ways (i.e. ways that aren’t immediately relevant to the subject/topic/theme the poem was already exploring) and see what happens when you revise the poem with these words in mind; or

Just dive into the revision with these sounds at the tip of your tongue—see what happens to the writing process when you are now aware of these sounds and start to make cuts, changes, and additions with them in mind.